Winter in the Vineyards: What Happens When Grapevines Sleep

A look at the anatomy of a grapevine and its winter dormancy

Mid-winter dormancy–a stage in the vineyards when time seems to stand still. Nature’s mute button has been pressed, swollen gray skies loiter above and chimney fires can be smelled from a mile away in the cool air. It is a beautiful time of year with a meditative Zen-like quality to it. Shhhhh, the vines are sleeping.

While last year’s leaves where still green on the vine, valuable carbohydrate reserves, which developed through photosynthesis, are now being horded by the woody trunk and roots. Because the grapevine’s metabolism level is currently next to nil, this energy source will prove vital in the spring when the vines wake from their winter sleep and reach for the stars.

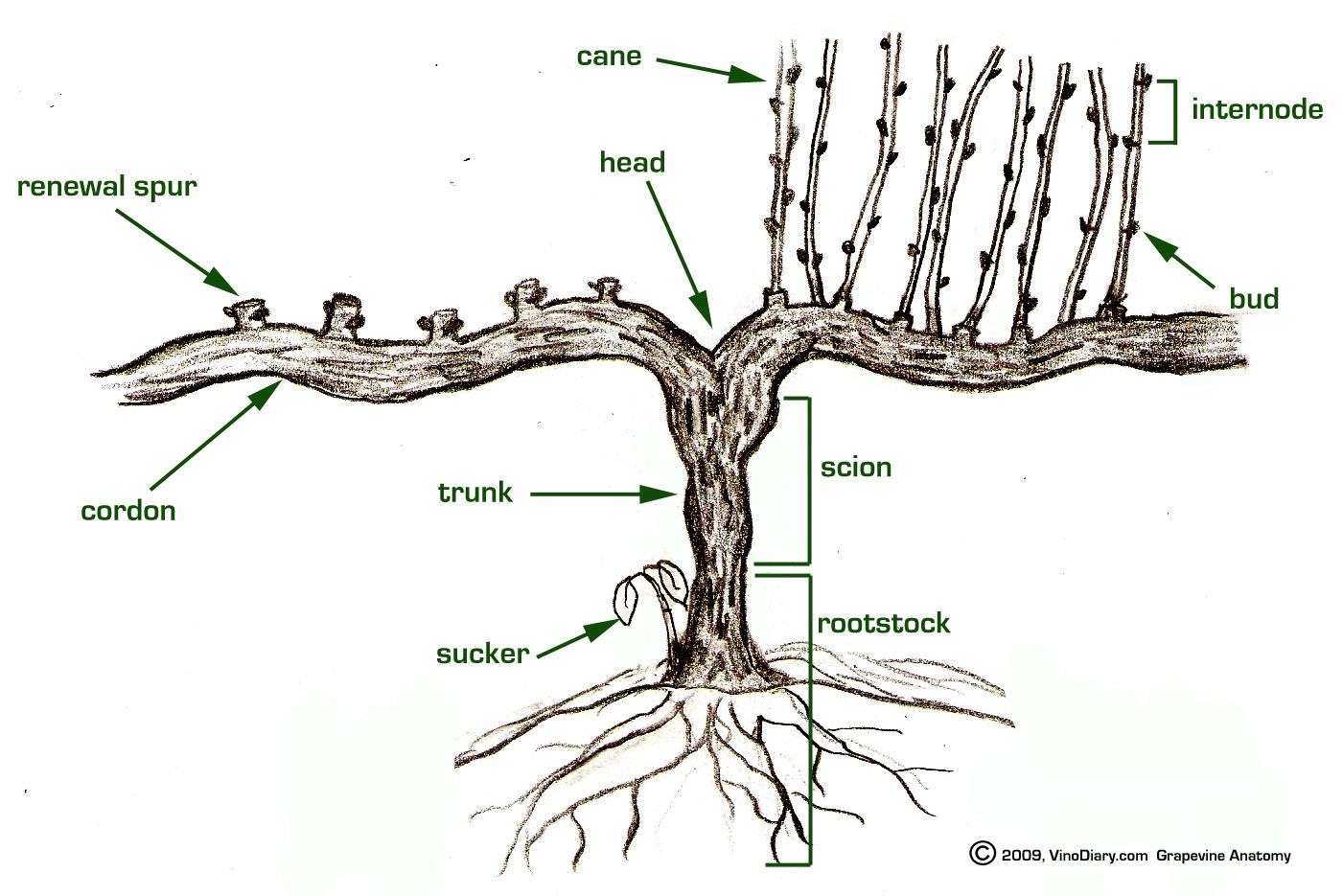

With the carbohydrates in the lower portion of the vine and no leaves to obstruct sight-dependent decisions, this is the perfect opportunity for grape growers to prune the vineyards. Winter pruning is the selective removal of canes—last year’s shoots that are now surrounded with a layer of wood—in order to facilitate the goals of vine training and canopy management. While there are different methods of pruning for various sight-specific conditions and varieties, the most common and familiar is spur-pruning on bilateral cordon-trained vines (just think of a “T” pictured above by VinoDiary). The trunk is the vertical part sticking out of the ground; the cordons extend from each side of the top of the trunk, and along the cordons are the vertical arms, spaced roughly four inches apart. Sticking out of each arm is a spur with two buds (usually). Each of those two buds will become this year’s two fruit-bearing shoots, which will be green for most of the season but will lignify (become woody) by next winter. Typically in pruning, depending on positioning, the higher of the two canes will be cut off, and the lower will be left as a two-bud spur, and the cycle continues.

Pruning is important to maintain the structural integrity of the training system. With bilateral cordon-trained vines lined up side by side, they become a continuous row with every single arm the same distance from the next, even between the last arm of one cordon and the first of the next. If we know the acreage of the vineyard block in addition to the row and vine spacing, and each arm grows two shoots, and each shoot grows two clusters (typically), then we can do a pretty good job of estimating the crop yield and the amount of wine that will be produced from it; that makes a lot of sense from a business standpoint. On top of that, having a nicely manicured row instead of a crazy bush makes the execution of the vineyard work much easier, and quite frankly, more aesthetically pleasing, which does hold merit.

Pingback: How to Prune Grapevines: Vineyard Farming for Wines - Journey of Jordan